How (not) to work with friends

Here's my guide of how to work and how NOT to work with and for friends.

The usual mantra in business is "never work with friends or family". More optimistic people say "turn your business partners into friends, but don't turn your friends into business partners".

Well, I've done both for over twenty years, and so far it's gone very well for me.

For context, I grew up working in two family businesses, so to say that the line between business and personal was blurry would be a huge understatement. Later on, I freelanced for friends and family (and a couple of fools, too) and then I created MarsBased with my two best friends from childhood. Ten years, 150 projects and more than 30 hires later, our relationship is the healthiest it's ever been.

The truth of the matter is that most people aren't skilled to work with close acquaintances because it takes a rare combination of honesty, resilience, and negotiation skills.

Disclaimer: This is how I have done it thus far, but it will most definitely not work for anyone else.

Let's start with the basics.

Know your relationship

I have always made two levels of distinction: best friends and just friends. Other people use the distinction of "real friends" vs "deal friends".

From Perplexity:

The distinction between real friends and deal friends has gained attention, particularly through the insights of Arthur C. Brooks in his book From Strength to Strength. This concept categorizes friendships based on their underlying motivations and emotional connections.

Real Friends: These are individuals with whom you share deep emotional bonds. Real friends know your vulnerabilities, support you unconditionally, and are there for you in times of need without expecting anything in return. They are characterized by genuine affection and a commitment to each other's well-being1 2.

Deal Friends: In contrast, deal friends are often seen as transactional relationships. These friendships are based on mutual benefits, where interactions may revolve around what one can gain from the other. Deal friends might help you advance in your career or provide social connections, but the depth of emotional intimacy is usually lacking2 3.

For Real Friends, I rarely work for or with. The few times I have done it, I have made it clear that I will work on the project if and only if I can't find anyone more suitable, it will have to be a short project and I will never work on it after my initial assignment.

This means, I will help you to set up your ecommerce, website or company, but I will find you someone else to work with you because I am doing this for little to no money and this erodes any relationship.

A commercial relationship is based on a discounted pricing for too long will erode from day one and eventually break.

By cutting ties early on, I minimise the chances of our relationship eroding, which normally comes as a consequence of the client asking for more and more things because this is cheaper than they expected - and because most of the times, you will overdeliver because you go the extra mile for your friends and family. Both things are understandable but short-sighted.

By asking to never work on the project again I might force my friend/relative to look for an alternative. Everyone sets their working conditions, so why shouldn't I? Some people set very high hourly rates, I set this instead.

Regarding price: I never ask for money from Real Friends nor relatives because I don't want to work for them: keep it short and disincentivise me from doing it. I want to help you quick and fast, but again: I will only do this if there's no one else in the planet that can do it. But I can gladly be paid with a good dinner or beer.

For Deal Friends, this is different. Here, I have always been more open for business, as most Deal Friends are replaceable if push comes to shove.

With Deal Friends, the downside (losing their friendship) is less critical than with Real Friends, so I'm more willing to take the risk. Deal Friends also have a better upside. They're much more likely to give you more projects than Real Friends.

Here, my conditions are even more strict than with Real Friends:

- I also take only very short assignments (4 weeks on average).

- I work on problems not tasks.

- I do stuff no one else can do.

- My price is that of a normal client or higher.

Again: I want to make sure you want to work with me. Otherwise, I will help you to find someone else.

Understand contracts and asymmetry of power

Before delving deeper into examples, let's talk about contracts.

On paper, contracts look like a good idea. We all know we should only work with contracts.

The reality is that I have never had a big problem working without a contract and I've had many small and big problems with contracts.

Contracts are a snapshot of a relationship that hasn't materialised yet. They're a long list of provisions that will set one part or the other ready for trial when things go south. Usually, the bigger/more powerful party will impose conditions and in most cases, contracts reflect a huge asymmetry of power.

A very clear example of that is when you work for a publicly traded company. They will impose their contract, with hundreds of clauses and provisions that only under very rare circumstances you will be able to negotiate or amend. And, if you decide to do it, you better be prepared to face an extemely long process of wear and tear of negotiation, dragging along for weeks (if not months) against multiple teams (legal, compliance, procurement and an army of contractor lawyers).

In a much more tangible example, you're a freelance designer and your income depends 100% on projects. If you haven't lined up your next project, you will have to negotiate your next gig with nothing on your plate, so your negotiation power is limited. The other party might know this because this is the reality of most freelancers and micro-agencies out there. They will impose budgets, deadlines and conditions.

On the other hand, if you have been working smart and have built a brand over the years, you might have the upper hand on the negotiation and set certain conditions. For instance, at MarsBased we impose our hourly fee and never discount it upfront. We couldn't do this for the first 3-4 years of our company, but now, we impose this, we impose working 100% remotely and that we don't do dailies.

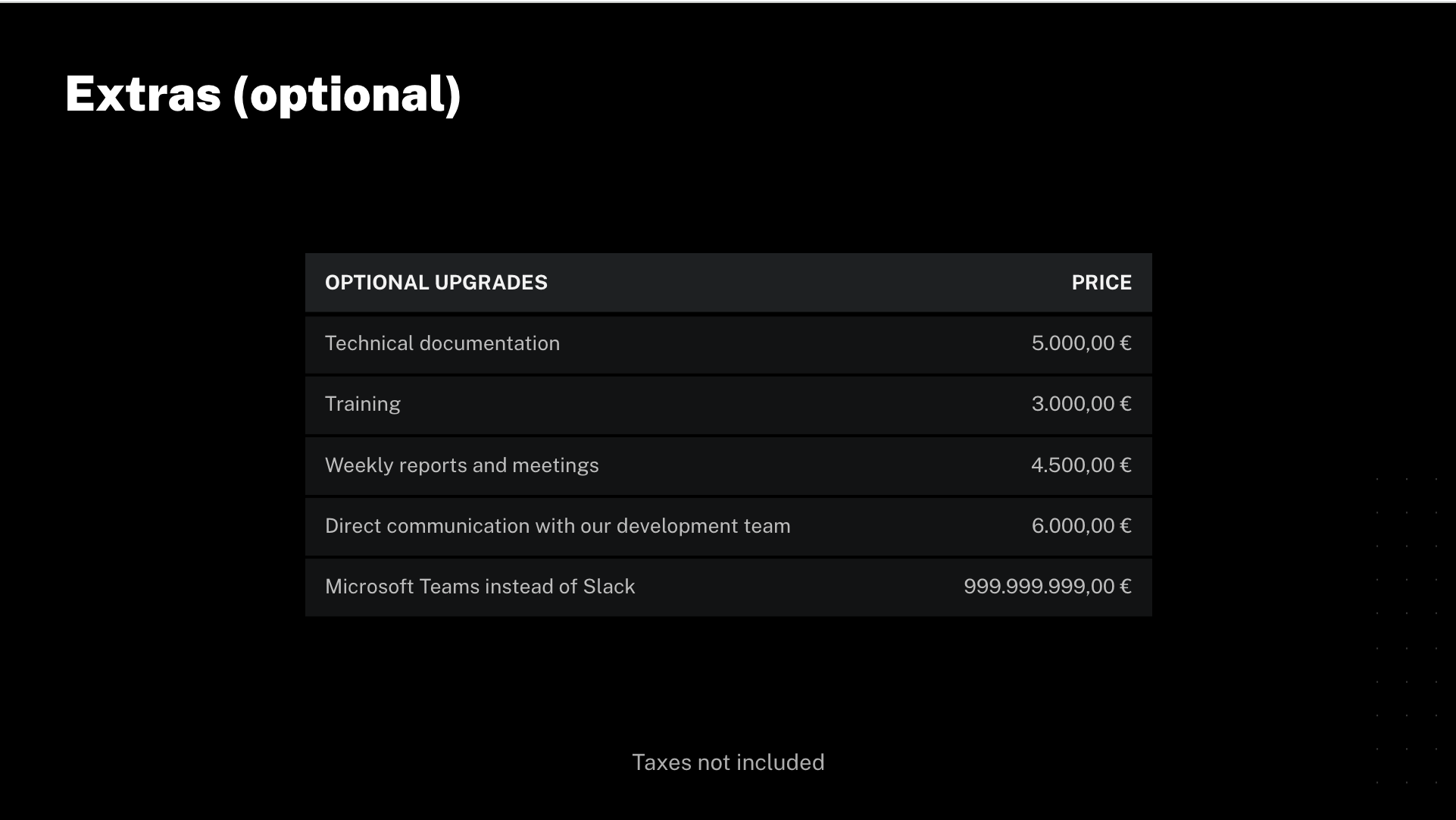

Look, in our template for quote documents, we have this slide:

Certain working conditions are an extra. If you want a cheaper project, we have to shave off management overhead. And if you want us to join your Microsoft Teams, there's an extra to be paid 😂

It is important to know what fights you can win. When I was a freelancer, I once worked for a private equity to do a scrappy project. This kind of companies are very strict on terms but they have fuckloads of money. When I presented my quote, they told me "how much would it cost to do it 2x faster?" - they gave me the hint that the deadline was not flexible, but money was. I charged 3x to do it 2x faster and they ok'd right away.

In another example, a few years ago we, at MarsBased, were approached by a friend working at a startup. They didn't have a lot of money so I helped them to find another company for that stage of the project. We would've been too expensive and they needed something scrappy to validate their business hypothesis, not to build something solid.

The project with this other agency didn't go too well but it helped them to get to the next stage, raise some funds and invest this time in someone better, so I got their call again.

Since I knew that a big quote would've worked against their runway, and that the project was a rewrite - so nothing urgent - I told them we could do it for 50€/h instead of the 70€/h (our rates at the time) if they could sign now and wait for six months to start the project. They accepted and we did the project. It was one of the best projects we've done to this day.

I could go on forever, but this is a perfect segway to discuss the next concept: price.

Set your price

Price is usually defined as the value that one party expects, requires, or gives in exchange for goods or services. Some might add the "... determined by market conditions" at the end of the definition.

For me, price is not a constant but a variable: when you're starting out it'll be lower, and as you grow in value, services, skills and portfolio, you will drive it higher.

But there's another consideration: it depends on your runway too.

Most people will start with a very low price (15-20€/h) to compensate for their lack of skills, and then increase it over the years, or project after project.

I never followed this strategy. I always freelanced on the side of a main gig, so I could cherrypick my clients and projects.

While I had to do jobs completely unrelated to my career (bartender, cleaning hotels, working in construction, teacher, etc.), they gave me a stable income and soft skills I wouldn't have acquired as a freelancer (teamwork, crisis management, planning, etc.).

By having a stable job, I could set my freelancer fee at 50€/h from the get-go. Most people didn't want to pay it, so I could sit for weeks without a project because I was not in a rush. Most people don't plan properly, and they start looking for a new gig when they've finished their current one, losing a lot of negotiation power.

Be also aware that your price sends also a strong signal about who you are and how you work.

A few weeks ago, I wanted to hire a frontend developer and I got a quote from a senior one with an hourly fee of 22€/h. I would've discarded it right away, but he came recommended by a friend, so I confronted him about why was the price so low and his reasons were not convincing, so I declined working with him.

Conversely, by setting my rate high from the get-go, I sent a strong signal to my potential clients that I was worth it or that I had a lot of work. That brought better clients.

Conflicts arise inevitably

Conflicts always appear. The longer a relationship, the more likely this will happen, as it's a natural part of the process.

At times we fuck up, other times it's the other party. At times it's a third-party and you're left to clean the mess with a nervous client.

While I prioritise long-term contracts for MarsBased with our clients, I think short contracts work better for freelancers.

There are three things you have to do to minimise the risk and impact of conflicts:

Analyse & communicate risks upfront

I learnt this at Deloitte, funnily enough. In our project proposals, we always included a "risks" slide. Since I started analysing risks and communicating them to the potential clients in the negotiation phase, I appeared more prepared to the client.

This analysis tells the client that you've researched the project, you've done similar things in the past and that you care about the relationship even before it starts.

Reevaluate often

Short contracts allow for more frequent renegotiation of terms.

As I mentioned, contracts are always asymmetric. Clients will never reveal all they know, so you have to guesstimate most of the times. They don't always do it out of spite or prudence: sometimes they really don't know everything about their project or company.

If you commit to a project for a year and the project turns out to be much more demanding or to have technologies you don't do, you're screwed. Renegotiating terms after signing them is nearly impossible.

By reevaluating every three months, for instance, you can sit with the clients and manage expectations better: tune up or down your dedication, add more time off in low seasons, leave things out of scope for the next project, etc.

For bigger projects, one thing we've done at MarsBased that can be useful is to add an initial audit at the start of the project.

In projects of extreme uncertainty, we add two weeks of initial assessment to research the entire project and reevaluate it. For instance, a two-years migration where we weren't allowed to see the code before signing the contract, we agreed on 15 days of audit at the start and we told the client that we could decline the project if we didn't see it viable, by contract. As a compensation, they'd have an audit of the project and a plan to find someone else. It doesn't always work, but you might want to give it a try.

Be ready to walk out any time

While the two considerations above work for both Real Friends and Deal Friends, this one is mostly for Real Friends: in case of conflict, I default to stopping the collaboration. For me, Real Friends are worth everything, and I'd rather keep the relationship than a project. No negotiation is possible. They might be slighly disappointed in the beginning but they have always appreciated my loyalty and my long-term thinking.

In the case of Deal Friends, it depends: is the conflict worth solving? is it a big deal? do you have other projects in the buffer? In these cases, I try solving the conflict first, unless it's a red flag for me or a repeating conflict over time where the other party clearly doesn't care about the relationship. In this case, it's good to walk out of the project and start the next one.

There's probably more stuff

This post is already too long, and it will probably turn into a guide.

I could think of ten other things to write about (communication protocols, tools, red lines, etc.) but I think this is a good starting guide.

Let me know what I should include in future iterations! Hope it's useful to someone!